The content strategy of civil discourse, part 5

In part four, we looked at the difference between hierarchical and collaborative conversations. Now we bring it all together and ask, “What can we do?”

The answer is, a lot. There are, as it turns out, many solutions to how we can do a better job of talking to each other, and any one of these are approaches you can try in your own lives or organizations.

Call Out Good Behavior

When’s the last time you saw a great comment in a comments section? Did you call it out? Tweet about it? Where is the “top ten comments of the year” list? The best comment award? The more you celebrate something, the more you’ll see of it.

And people will begin to compete. It’s in our nature. If we know there’s a best or most civil comment award out there, we will try to win it and it will affect how we comment.

Similarly, let’s call out positive outliers. This whole series began with a story told by a co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network, who makes it their business to call out well-investigated solutions that are steps in the right direction. I myself have attempted to remedy the opposite-results problem I highlighted in the last post around looking for “movies that will make me less racist” and only getting lists of racist films. I created the #WokeCinema hashtag, and for one year, I used that hashtag to post one film a day that I thought did a good job of portraying or talking about race, gender, or some other social issue. Given that if you search for the hashtag you will almost exclusively see my posts, it wasn’t “successful,” but it was my attempt to add to the how content bucket and not just the how not to bucket.

Civil Comments

Civil Comments was an app that allowed you to make commenters rate three other comments before posting their own. This did three incredible things. One, it forced users to acknowledge that there was such a thing as good or bad comments. Two, it forced them to apply their own standards to what that is. This is powerful because we will adhere to our own standards far more readily than we will to anyone else’s. So when a commenter rates someone else’s comment poorly and then sees the same problem with their own comment, they have to go back and change it because the cognitive dissonance of not living up to their own internalized standard becomes too great.

And, finally, they know that if they’re rating other people’s comments someone else will probably end up rating theirs so they feel compelled to up their game. All of these elements conspired to make many commenters who used the system go back and change their comments after rating others’ comments.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that Civil Comments is no more. At the end of the day, they failed to find a sustainable business model. When I told this story to Chris Alfano, a founding co-captain of Code for Philly, he said…

“We need more tools than there are business models for.”

Some of these fixes may need to happen because they need to happen, even if, in business terms, they are a cost center.

A 14-Year-Old Solves Twitter

Trisha Prabhu was 14 years old when she won the Google science challenge with the ReThink platform that reduced teen hate-posting by 93%! How did she do it? Very simple. Let’s say you’re on a social media platform using the ReThink technology. You’re about to post a hateful tweet. ReThink catches it and when you hit send it pops up a screen that says “ReThink has detected that this message may be hurtful to others. Are you sure you want to post this message?” 93% of adolescents who saw that intervention didn’t post.

This tells us two things. First, most of the people out there aren’t evil, they’re just thoughtless. As soon as you remind them that there’s a human being on the other end of that post, they straighten up. Second, it only takes two sentences to stop them. Two. Sentences. Here we are lamenting the state of social media, convinced it’s an unfixable problem. Two sentences! From a 14-year-old. Taking out 93% of the problem. We can do this.

Ask the Right Questions

We talked in part one about the Convergence Center for Policy Resolution, who brings people together from opposite sides of an issue to find solutions. Part of their special sauce is the way they craft the questions they ask. Let’s say the issue was food deserts. They might ask, “How can we get healthier food into the supermarket?” However, believe it or not, this is a very divisive question. Instead, they would ask, “How can we work together to shift consumer demand to healthier consumption?”

See what they did there?

The very question, by how it begins, forces you to work together. You can’t answer the question without also figuring out how to do it together. And look at the phrasing, “shift consumer demand.” If I’m a marketer and I hear the words “shift consumer demand,” I’m already thinking about white spaces and untapped market share and I’m on board. If I’m a health advocate and I hear “healthier consumption,” I’m on board because that’s what I’m all about. If I’m a food store owner, I see the terms “consumer demand” and “consumption” and think, I need to be a part of this. Everyone can see themselves in how the question is phrased and is therefore more willing to take part.

What about the question that started this whole thing, “How might this person drive this car?” It’s a good enough question insofar as it goes. But what about, “How might we do a better job of moving people around?” That’s the reason the person was in the car in the first place. They were here and they wanted to be there. Now solutions like public transportation are on the table.

Thinking Beyond Comments

A few years ago, NPR got rid of their comments section on posts. They didn’t do this because they were throwing up their hands and saying, “this is why we can’t have nice things.” They were doing it because they already had a dozen better ways for people to talk to each other, including…

- 30 Facebook pages

- 50 Twitter accounts

- Snapchat

- Tumblr

- Facebook groups

- Personal social accounts

- Contests

- An audience relations team

- And a good, old-fashioned ombudsman

With all of that, why rely on an ineffective means for people to express themselves to NPR and each other? We should continually rethink if we’re using the right tools for these conversations, and adjust as needed.

Create New Platforms for Better Conversations

And where the old platforms just aren’t getting it done, let’s create new ones. GitHub is a platform where people can collaborate on code. What if we had a similar platform where folks could collaborate on ideas? Here’s what that might look like:

Let’s say I see something that upsets me on Facebook. I could debate about it in the comments. I could react with an angry or sad face. But what if there was a lightbulb icon? What if there was a “collaborate to make this better” button? And what would happen if I pressed that button?

Well, in the real world, it might look something like this:

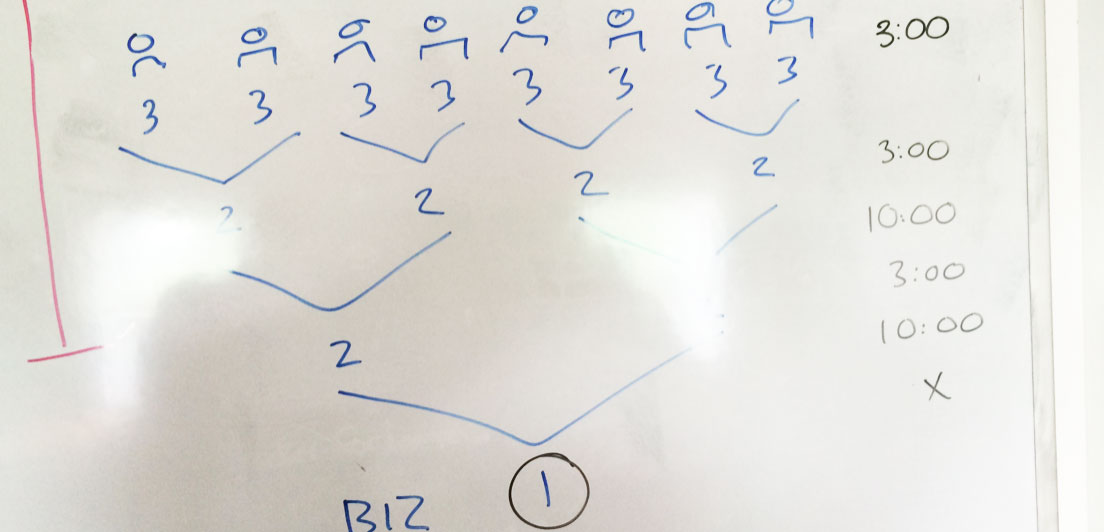

I call this an “8-up” exercise and it works something like this.

You get 8 people in a room and you ask them a design question like “How might we do a better job of moving people around?” Then you say “You each have three minutes to come up with three ideas for how we might do a better job of moving people around”

Those three minutes pass and now all 8 people have three ideas each. You then say, “Great, now turn to your neighbor, show them your three ideas, they will show you their three ideas, take those six ideas and whittle them down to two.”

After they’ve done that, you say to each pair, “Okay, show your two ideas to the pair next to you. They’ll show you their two ideas. Take those four ideas and whittle them down to two.”

After that, you’ll have two groups of four with two ideas each. You get all eight people together and say “Take those four ideas, and whittle them down to one.”

This tends to produce better ideas than just saying “Hey, eight people, come up with ideas and we’ll vote on the best one” or “Hey, eight people I’m gonna lock you in a room until you agree on an idea”. Either of those approaches tends to produce mediocre ideas, but combining those approaches tends to produce great ideas.

I’ve run this exercise with numerous clients on numerous occasions, but always in person. It works very well in person. The question is, is there a way to do this online? That’s what would happen when I click on the “ideate” button.

I encourage the coders and designers among you to get to work on this.

Use Design Language for Something Other Than Design

There are phrases and approaches that design and development use to help build things. One of these is a user story. A user story describes a feature in a way that allows a designer and a developer to create a vision and requirements for what needs to be built. It usually follows a format like “As a _____, I would like to _______, so I can ___________.”

So if we were building iTunes we might say, “As a listener, I would like to recommend music to my friends, so I can look smart.” But what if we used this language for more pressing issues?

“As a woman, I would like to be paid as much as a man, so I can pay off my student loans.”

This puts a major social issue into a more actionable context and starts to give us a framework for the vision and the requirements for building tangible, goal-oriented solutions.

Explore Problem-Based Procurement

Typically the process for procurement (a city getting the things that it needs) goes something like this: “We need new streetlights so we’re going to create an RFP that details in 50 pages every jot and tittle of what needs to be in those streetlights—how many of them there need to be per mile of road, exactly how many lumens they need to put out, how high they need to be off the ground, how much wattage they use, etc.—and we’ll put that RFP out to the same five vendors who always bid on this sort of thing and award the contract to the one who comes in lowest.” This gives you predictable, but not necessarily the best—and certainly not the most innovative—results.

Problem-based procurement says let’s put out an RFP that just says, “We need to be able to see at night.” That’s it. Best solution wins. Now, if it turns out that buying everyone night vision goggles is actually the most efficient solution, we get to do that. And anyone can play. This is another instance where framing the problem (instead of presuming the solution) can create better collaboration and better results.

This approach is actually being implemented in cities around the world, including Think Company’s hometown of Philly!

Use Design Approaches

A lot of what I’m talking about here just boils down to good old fashioned design thinking which, when you boil it down to its essence is: Before you build something for somebody, talk to them first. We should pursue this not just with websites but with policies. Before we design a policy for someone, talk to them first. Before we design a service for somebody, talk to them first. Again, cities around the world are beginning to incorporate human-centered design into their operations and approaches to problem solving for citizens.

“Marvelous technology is at our disposal and instead of reaching up for new heights, we try to see how far down we can go.” — Eric Bogosian, “Talk Radio”

This quote is from the 1988 film Talk Radio in which Eric Bogosian plays a shock jock radio personality but the technology he’s talking about might as well be the internet and social media. So how can we reach up for new heights? I recommend three rules to follow going forward…

(And here I am quoting from a previous Medium post of mine…)

Rule #1: Neither of Us Has the Answer

This assumes that if we had the answer, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. Climate change would be solved. The refugee crisis would be handled. Women would have equal pay. We would have nothing to talk about.

But we do. We quite obviously have something to talk about so let’s talk about it, not assert our own point of view about it. Let’s go in assuming that neither of us knows everything about the topic nor do we have the silver bullet for it already waiting in our pocket and we just have to convince the other that it IS the silver bullet. Instead let’s assume our mutual ignorance. Let’s assume that we’ll both learn something.

Rule #2: Neither of Us Will Win

This is a very difficult rule. We go into these conversations assuming there has to be a winner. One of us will come away convincing the other that we’re right. Or one of us will come away at least feeling like we made a better argument.

But in this type of conversation, winning is not what we’re here to do because winning doesn’t actually solve anything. That’s the myth. We think if we win, we fix it. But we don’t. Winning just makes one of use feel better for a little while until the problem we were fighting about rears its ugly head again because we were too busy winning to actually solve it.

Rule #3: We Are Here to Create Something New

This reinforces the assumption that neither of us has the answer. It allows us to abandon the idea that we’re here to take something old and beat the other person over the head with it until they agree it’s right.

No, we’re here to take our collective knowledge and experience and create something that neither one of us has ever seen before. Because it’s going to take something neither one of us has seen before to get the job done. If not, we’d have seen it already and the job would be done. This assumes that we both have something of value to contribute to the outcome. This assumes the best in each of us, and not the worst.

So, with these rules in mind, let’s see if there are more opportunities for us to turn conflict into collaboration.

Bonus: I am telling a version of this story at SXSW—Content Strategy Hacks to Save Civil Discourse. If you’re going, I’d love for you to come out to see it, and stop to chat if you can.

(You can also see these rules as a TED talk here…)

Did you know Think Company offers this series as a talk for teams, events, and conferences? If you’re interested in learning more, get in touch with us via our contact form.