The Innovation Coefficient

Designers and product managers should be obsessed with observing how their communities use their products. They should be fascinated with the differences between what they intended to design and what the community gets out of it. It’s easy to pay lip service to that principle, but harder to make it the focus of your work.

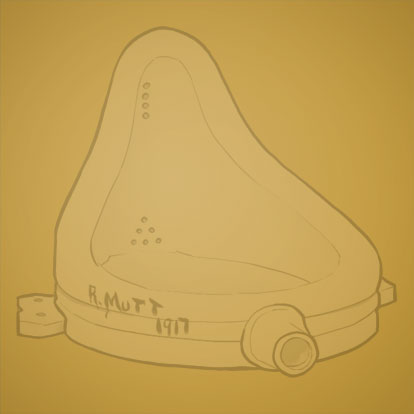

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp submitted an art piece titled Fountain to an exhibition. It was an upside down urinal signed R. Mutt, 1917. The piece was part of a series he called Readymades. His work was rejected by the exhibition and, almost a century later, continues to be debated in art history classes around the world.

What was this accomplished cubist/modern artist trying to do and what does it have to do with experience design? We get some insight by reading Duchamp’s essay The Creative Act where Duchamp explains his fascination with the specatator’s reaction to art.

…the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.

In this essay, Duchamp also introduces the concept of The Art Coefficient:

…the personal ‘art coefficient’ is like an arithmetical relation between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed…

Experience designers have a similar practice I’ve started to refer to as the Innovation Coefficient. Anyone who has designed or built anything has had a very specific idea of how the user should interact with their product. The Innovation Coefficient is the difference between what you intended to be done with your product and what the user actually does with the product.

To track the Innovation Coefficient you must become obsessive about observing your community of users. Watch what they are doing with competitive and analog products as well. Run usability studies; monitor analytics; convene advisory panels; read product forums; avoid putting the “I in ‘design.'” The more often something is observed, the higher the Innovation Coefficient. Propose features that are observed through repeated hacks, behavioral patterns, and direct user requests.

Designers and Product Managers who encounter the Innovation Coefficient can react one of two ways: embrace it or fight back. Usability Guru Don Norman refers to fighting back as “Blame and Train.” In other words, fighting back is a fool’s errand. Here are two ways to embrace the differences.

Cowpathing: Embrace Unintended Uses

When Twitter first launched it was not very feature-heavy. Send a text message to 40404 and it would appear in a searchable public feed. Users started mashing words together and adding a hash symbol (#) to make search more powerful. They did similar things with the @ symbol to identify other users.

Twitter could have tried to tweak their search functionality to meet the needs of the user and get rid of all the #’s and @’s cluttering their newsfeed, but they didn’t. They chose to embrace the change and built #hashtags and @naming into their designs. The result: when we see a hashtag, we want to click to execute a search (well, some of us anyway). Facebook, Instagram and most other social media tools adopted the functionality. In 20 years we may still be using hashtags but, like parking lights on your car, few people will know their origin.

Landscape architects and usability experts call this cowpathing. Rather than laying out a series of paths and sidewalks in a new landscape, don’t put in any paths. Visitors will wear out the grass in the patterns of their typical commute. Once you know where people are walking, pave the cowpaths. The result may be more organic and less symmetrical than originally intended, but your design also won’t be cluttered with fences, hedges and “Keep off the grass” signs.

Cowpaths are the formalization of the Innovation Coefficient. Ask yourself, “What would Marcel do?” He wasn’t curious about other artists, gallery owners or art critics, he was curious about his spectators.

Product Management using Innovation Coefficients

Most modern product teams target features that are absolutely necessary to release a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Product managers listen to analysts and watch their competition to identify new features and add them to a backlog. The result is a cluttered matrix of features, strategies and estimates. For the life of the product, your team will slowly chip away at a backlog that is always growing. Your community needs will always evolve faster than you can address items in the backlog.

There is a better way, and it starts with burning your backlog.

Go ahead and release your MVP, then spend your energy observing user behaviors. When it’s time to work on an update, focus on features with a high Innovation Coefficient.

If you already have a backlog of features, gauge their Innovation Coefficient before making a decision. Throw out whatever doesn’t make it into a release and start over again. Watch competitors, but don’t chase them. If their features are valuable to your users, your users will let you know. Marcel may have cared that Picasso went through a blue period, but that is not what made him curious and he certainly didn’t go through a blue period himself.

Where is the Innovation?

Many argue that large organizations are incapable of innovation; I’m not in that mindset. I am often concerned that large organizations pay attention to the wrong sources in order to innovate. Of course new ideas can come from within and they should be explored. Making a strategic decision to expend all of your energy hoping your ideas will catch on is ignoring your greatest innovative asset – your community of users. As Charles Leadbetter explains in this TED talk, mountain bikes were invented by a community of hackers, not the R&D department at Schwinn or Raleigh.