Designing Better Play

A few months ago I took my 2-year-old son to the Phoenix Children’s Museum. Like the ideal Pixar movie, it offered a near perfect blend of pure fun, ah-ha moments, and creative inspiration. In fact, I’m pretty sure my kid was dragging me home. But even more memorable than the noodle forest and pneumatic hankerchef delivery system was a shuttered room with a sign that said, “Experiment in progress: we’re designing new ways to play”.

It seems almost counterintuitive to “design” play. We often associate play with spontaneous fun that’s, at most, bounded by a loose set of ground rules (e.g. no hair pulling) that can evolve as needed. But in many ways, today’s playgrounds are designed with a heavy hand and a few too many dashes of bureaucracy. American playgrounds have morphed into spongy turf areas filled with bulbous plastic structures that offer up ready-made, predictable experiences. These structures are meant to restrict (read “protect”) as much as entertain… let alone inspire.

It’s true, on one level cities pressed by budget constraints face issues like liability and upkeep, which in turn drives the eventual lowest-common-denominator form playgrounds take. But on another level, these generic playgrounds seem designed with an insidious checklist mentality—can kids swing? check; can kids climb? check; is there a tunnel? check; will parents think its safe? check. As we all know, a checklist does not fun make.

To design play well, we should start from a different mindset. A tunnel is not inherently fun. However, crowding into a tunnel with others and collectively squishing a beach ball through it could be. Here a tunnel becomes a congregation point that supports a variety of fun and unpredictable activities. So the question guiding the project becomes: how do we create a series of similarly inviting spots that encourage inventive play? Or better yet, how do we enable the kids to create those spots for themselves?

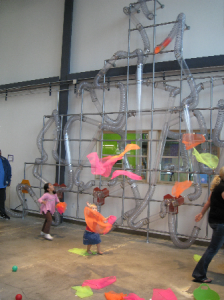

In The New Yorker, Rebecca Mead wrote about a new breed of “interesting” playgrounds appearing in the city. One of the examplars is Imagination Playground designed by David Rockwell. The key difference from the “uninteresting” playgrounds is replacing fixed equipment with a battery of loose parts. Kids can use these parts to fashion all types of things from forts to game areas. This type of set up encourages collaboration, sharing, and a sense of collective accomplishment.

As Mead described in a podcast, this park includes a “play worker” or coordinator, someone who oversees the park and is there to help children learn to play. Instead of being overbearing, this person is meant to help liberate the kids from their parents’ intrusive (but well-intentioned) mediation. This allows the kids to figure out how to accomplish things themselves while also enabling self-direction and invention. In other words, this more loosely structured playground actually offers more freedom for imaginative play and, in turn, more challenges for kids to puzzle through than the traditional one that attempted to anticipate and cater to their perceived needs.

Naturally this principle applies to broader creative challenges, too. Creating a supportive, collaborative environment where ideas can grow in unanticipated ways will, at a minimum, lead to a more engaged team and, ideally, better end results. As design “coordinators,” enabling others to think creatively themselves (while having fun doing it) will allow everyone tackling a problem to quckly jump past the generic solutions toward the more “interesting” or appropriate ones. For everyone who’s part of the creative class, it’s up to us to discover and teach others “new ways to play”. It’s serious business.