Reflecting on Assistive Technology and Advocating for Accessibility

In 2015, the percentage of people in the U.S. with disabilities was 12.6%. To put it another way, nearly 40 million people out of roughly 317.5 million individuals in the United States reported one or more disabilities.* How do these millions of people interact with technology? What’s being done for them?

I had the opportunity to learn more about accessibility when I attended this year’s CSUN Assistive Technology Conference. CSUN, as it’s known, is held by California State University’s Northridge Center on Disabilities. For over 30 years, the Center on Disabilities “has provided an inclusive setting for researchers, practitioners, exhibitors, end users, speakers and other participants to share knowledge and best practices in the field of assistive technology.”

What is assistive technology?

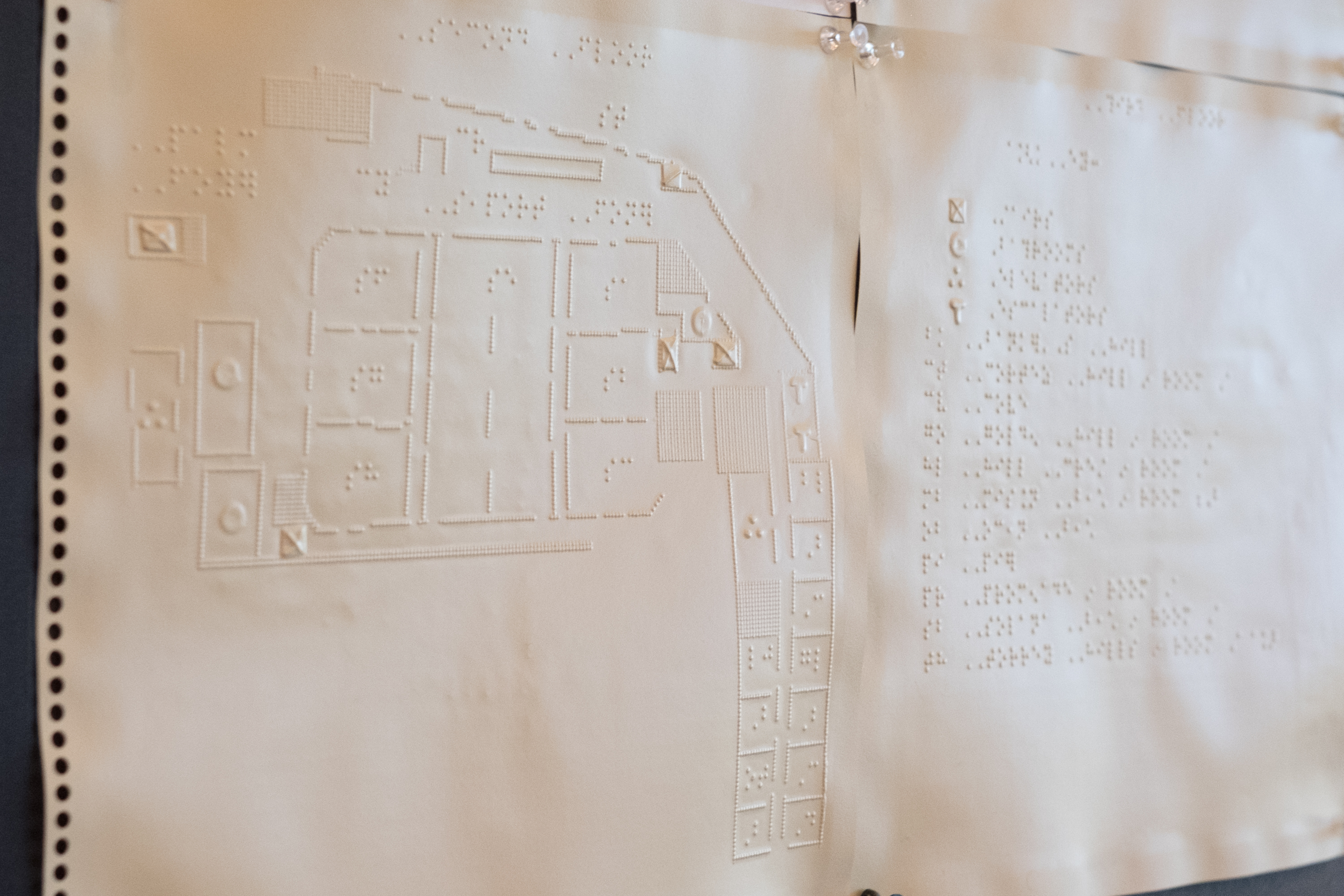

AT (as it is commonly abbreviated) is a broad term. Essentially, it encompasses all the devices and technology people with disabilities use to achieve greater independence and perform things they might otherwise be unable to. Everything from hearing aids and wheelchairs to screen reader software and electronic braille devices are considered AT. In the context of what we do, AT includes the tools used to achieve web accessibility.

Like many organizations, we group the accessibility needs of our users into four areas:

- Visual: Users with all forms of color blindness and visual impairments. These users might have difficulty discerning certain color combinations or rely on screen magnification software and/or screen readers.

- Auditory: Low hearing or deafness. Individuals who are hard of hearing would have difficulty with information presented without text, such as videos without closed captioning. In most cases, CC would be enforced by law.

- Motor/Mobility: Difficulty or inability to use hands for any reason. Loss or lack of fine muscle control would also be categorized under mobility considerations.

- Cognitive: Developmental disabilities, learning disabilities, dyslexia, ADHD, and other cognitive disabilities of various origins affecting memory, attention, problem-solving, and logic are all grouped together. From the perspective of a designer or developer, I find this one to be the most challenging as it is the least tangible and most broad.

When sites and applications are designed or developed while considering these factors, the barriers that people with disabilities encounter are removed or never created to begin with. Dr. Kellie Lim, CSUN’s Keynote Speaker, phrased it, “If the environment fits you, then you have no disability.” Jamie Knight reinforced this concept in his Cognitive Accessibility 103 session when he stated that people are not disabled, people are impaired. Experiences disable impaired people. “As designers, we disable people when we don’t get it right,” he added.

I’ve observed that the driver for accessibility is often the prevention of legal action. If a person is unable to achieve a simple task such as paying a bill or accessing important records due to a site design, it’s a critical problem and a legal risk. When solving these issues, I’d encourage everyone to take it several steps further. Legal compliance doesn’t ensure a pleasant experience. Just because something is accessible, or possible, doesn’t mean it’s joy to use. It should be.

AT as an extension of UX

As I see it, accessible design is an extension of the user experience. When we consider designing for accessibility, we’re considering a wider range of experiences. How confidently can we consider something usable if it’s not entirely usable by a whole host of people? What kind of easy, common mistakes can we avoid? Unless we’re careful, the people we’re designing for might be unable to achieve even the simplest of tasks.

How do we not only enable people but also empower them using technology?

It’s not easy. I’ve found that in our industry, accessibility is still often a mystery. As my colleague Brittany previously shared, there are even some common myths to dispel when it comes to designing for accessibility. A shift in mindset and consideration is the first step to creating more accessible experiences.

Accessibility By Everyone, For Everyone

In her CSUN talk, “Integrating #a11y in Dev Workflows,” web developer and accessibility advocate Marcy Sutton wrote up many actionable ways every person in a process from Product Owners to QA testers can ensure and consider accessibility. Software developer Job van Achterberg echoed these sentiments in his session, “Automatica11y: Trends, Patterns, Predictions in Audit Tooling and Data,” by professing, “I don’t want to be the accessibility person on the team. I want everybody to be the accessibility person on the team.”

Being mindful of accessibility allows us to create a better, more holistic user experience and improve our goodwill for our fellow humans. We should do good for the sake of being good. Or in a more Think Company-specific way of putting it, let’s be excellent and be nice to people.

In some cases, depending on the situation, we can even use accessibility concerns as the reason to refine, clean, and produce better code since so much AT depends on it.

At CSUN, I was able to interact with and be around not only other technologists in my field, but also many people across all-things-accessibility: designers, developers, researchers, advocates, and end users. Hearing from accessibility professionals and being around end users has been a huge influence and motivator for me as we work toward creating more accessible experiences. I get the sense that users who depend on AT are treated as edge cases. That may be true, but if we design for all the edge cases then the “middle case” will hopefully fill in on its own.

In Conclusion

What I’ve been able to gather is that being mindful of accessibility requires us to consciously think about the types of barriers we place, intentionally or accidentally, and how to remove them. And when we’re designing, we should consider a diverse group of people and account for the edge cases. If we’re successful, the result will be an experience that’s pleasant for everyone.

How are you considering assistive technology and accessibility in your work?

* 2015 Disability Status Report United States, Cornell University, https://www.disabilitystatistics.org